Der Sommer 2024 könnte als neues Rekordjahr für den europäischen Tourismus in die Geschichte eingehen – insbesondere für den Tourismus auf der Schiene. In West- und Südwesteuropa spricht man von einer Renaissance des Nachtzugs. Urlauber aus dem D-A-CH-Raum sollen in den kommenden Jahren die Möglichkeit haben, klimafreundlich mit dem Zug bis nach Barcelona und weiter an die Costa Brava zu reisen.

Während im Westen eine Renaissance gefeiert wird, hat der Nachtzugverkehr im osTraum eine lange Tradition. Die Sowjetunion besaß einst das größte Nachtzugnetz der Welt, das Moskau mit nahezu allen Teilrepubliken in direkter Verbindung verband. Bis zum Ausbruch der Corona-Pandemie gab es sogar eine direkte Zugverbindung zwischen Berlin und Moskau. In vielen Regionen des östlichen Europas ist der Zug nach wie vor ein unverzichtbares und oft benutztes Verkehrsmittel.

Heute tauchen wir in die faszinierende Welt der Eisenbahn im osTraum ein und präsentieren sieben Bahnstrecken, die sich ideal für die Urlaubsplanung oder einen spontanen Ausflug eignen. Diese Strecken bieten nicht nur bequeme Reisemöglichkeiten, sondern auch einzigartige Erlebnisse und atemberaubende Landschaften.

Die Elbtalstrecke: (Hamburg – Berlin -) Dresden – Prag (- Bratislava – Budapest)

Die Elbtalstrecke ist ein kurzer Abschnitt, der kurz nach Dresden von der Sächsischen Schweiz bei Bad Schandau über Děčín und Ústí nad Labem bis zu den Vororten von Prag führt, wo die Strecke dann entlang der Moldau in der tschechische Hauptstadt für manche Züge endet. Es gibt aber auch Züge, die bis nach Budapest fahren. Auf dem Weg nach Prag bekommt man spektakuläre Aussichten zu sehen, von Bergen und Burge, bis hin zu der Industrielandschaften von Ústí nad Labem.

Die Strecke wurde 1850 erbaut, vorerst nur bis Děčín, an die Grenze des damaligen Habsburger Reiches. Später folgte die Erweiterung nach Dresden, was die heutige Strecke ausmacht. Bekannt ist sie auch dafür, dass sie im Jahr 1989 für die drei Ausreisewellen von DDR-Bürgern aus Prag in die BRD genutzt worden ist, nachdem der Außenminister Hans-Dietrich Genscher vom Balkon der BRD-Botschaft in Prag die Genehmigung der Ausreise verkündete.

Heutzutage ist die Elbtalstrecke teil eines der wichtigsten Korridore im osTraum. Auf der Strecke verkehren Züge von Hamburg bis nach Budapest und decken vier Länder und deren Hauptstädte ab. Einst eine Eisenbahnmagistrale der Habsburger, und später im Ausbau eine Magistrale des Warschauer Paktes, ist die gesamte Magistrale heutzutage weiterhin eine wichtige Ader in Mitteleuropa. Und die Elbtalstrecke bildet den schönsten Abschnitt auf den langen Reisen der Passagiere.

Die Landbrücke: Rzeszów – Lwiw – Kyjiw

Seit Anfang des russischen Angriffskrieges auf die Ukraine musste die Zivilluftfahrt eingestellt werden. Mit Europas zweitgrößtem Nachtzugnetz war die Ukrainische Bahn für den Anstieg der eigenen Passagierzahlen vorbereitet. Die Strecke von Rzeszów in Polen bis zur Hauptstadt in Kyjiw wird von Geflüchteten, Hilfsorganisationen, Staatschefs, und zunehmend auch Touristen genutzt. Die Bedeutung der Strecke liegt nicht in schönen Aussichten, besonderen Konstruktionen, oder interessanten Zügen, sondern in etwas viel wertvollerem – den Mitreisenden. Sie ist oftmals die einzige Verbindung für Familien, für humanitäre Hilfe, aber auch für Journalisten, um direkt aus der Ukraine heraus zu berichten.

Anmerkung: Obwohl sich die Sicherheitslage auf der Strecke zunehmend verbessert, befindet sich die Ukraine weiterhin im Kriegszustand und die Außenministerien der EU-Länder raten davon ab, die Strecke bis Kriegsende zu nutzen.

Der Eurovision Hit: Chișinău – Bukarest

Hop! Hop! Let’s go! Beim Eurovision Song Contest 2022 trat Moldawien mit dem Pop Folk Song „Trenuletul“ (der Zug) an. Der Song landete auf dem 7. Platz, bekam jedoch die zweitmeisten Publikumsstimmen (nach der Ukraine mit „Stefania“). Der Song dreht sich um den Nachtzug zwischen Chișinău und Bukarest.

Heute von Influencer*innen aus aller Welt auf Instragam und TikTok als „der letzte sowjetische Nachtzug“ beworben, war die Strecke von Chișinău nach Bukarest ein Pilotprojekt der Sowjetunion, die Teilrepublik Moldawien mit dem sozialistischen Rumänien per Schiene zu verbinden, und somit eine Verbindung für die Familien herzustellen, die sich nach dem zweiten Weltkrieg in zwei verschiedenen Ländern vorfanden. Das alte Rollmaterial ist tatsächlich heutzutage noch unterwegs, und die kulturelle Signifikanz des Zuges hat auch nicht abgenommen.

Ein Highlight der Strecke ist auch der Spurwechsel. Da die Spurbreite der Gleise in Moldawien dem sowjetischen Standard (1520mm) entspricht und in Rumänien dem europäischen (1435mm), werden die Waggons an der Grenze in einer Werkstatt angehoben, damit die Räder ausgetauscht werden können. Dieser Vorgang passiert während die Passagiere im Zug sitzen, und ist eine der letzten Stellen auf der Welt, wo der Spurwechsel noch mit dieser Methode durchgeführt wird.

Die Adria-Magistrale: Belgrad – Bar

Der Balkan hat im gesamten osTraum die am wenigsten ausgebaute Schieneninfrastruktur. Unter anderem weil das ehemalige Jugoslawien, im Vergleich zum Warschauer Pakt weniger auf die Schiene und mehr auf die Straße und Individualverkehr gesetzt hat. Dennoch träumte man schon seit 1896 von der Adria-Magistrale um eine Verbindung zwischen dem serbischen und montenegrinischen Königreich herzustellen.

Erst in den 1950er Jahren wurde unter Tito der Bau angestoßen, und nach mehreren Etappen war 1976 die Strecke vollständig, als der Abschnitt von Titovo Užice (heute: Užice) und Titograd (heute: Podgorica) mit der höchsten Eisenbahnbrücke Europas, fertiggestellt wurde. Symbolisch fuhr Tito mit seinem Blauen Zug zwischen den zwei Städten, die seinen Namen trugen, und weihte die Strecke offiziel für das Volk ein.

Die Strecke ist ein Sommerhit für die Belgrader*innen, die in ihrer Stadt einschlafen und an der Adria am nächsten Morgen aufwachen konnten. Für die Arbeiter im damaligen Jugoslawien wurden sogar Sonderzüge an die Küste organisiert. Heutzutage ist der Zug eine wichtige Verbindung für Urlauber und Abenteurer. Im Sommer fährt eine Verbindung tagsüber, die nicht so glamourös ist wie der Nachtzug, dafür aber die Möglichkeit gibt die gesamte Schönheit der Atemberaubenden Strecke durch die dinarischen Alpen zu genießen. Zwischen Kolašin und Podgorica ist die Strecke am höchsten, sogar bis zu 1200m über dem Meeresspiegel. Dort findet man auch die höchste Eisenbahnbrücke Europas.

Die Kaukakusbahn: Jerewan – Tbilisi – Batumi

Wer braucht schon Barcelona, wenn es Batumi gibt? Die georgische Hafenstadt ist eines der meistbesuchten Badeurlaubsziele im gesamten osTraum. Um dem Passagierstrom gerecht zu werden, baute die Georgische Bahn eine Schnellverbindung zwischen Tbilisi und Batumi und fährt mit modernen Doppelstockzügen durchs Land.

Die besondere Verbindung ist jedoch die Kaukasusbahn, die im Sommer von Jerewan, über Tbilisi, bis nach Batumi führt. Im Winter ist ein Umstieg in Tbilisi notwendig, weil das Fahrgastaufkommen nicht groß genug ist. Durch Berge bis hin zur Küste, auf der Strecke sieht man alle Landschaftstypen, die für den Kaukasus üblich sind. Auf dem Weg begegnet man den verschiedensten Menschen aus der Gegend, sowie den verschiedensten kleinen Orten an welchen der Zug hält.

Die Habsburgerbahn: Wien – Budapest – Bukarest

Obwohl Bukarest nie unter der Kontrolle von Österreich-Ungarn stand, ist ein spannendes Bahnnetz im Dreieck Österreich, Ungarn und Rumänien entstanden. Zu der Zeit der Habsburger hat man am Schienenausbau gearbeitet, so auch im Banat und in Transsylvanien, die (teilweise) heutzutage Rumänien gehört. Rumänien selbst hat dann die alten Habsburger Strecken in das eigene Schienennetz integriert und ebenfalls ein beachtliches Nachtzugnetz aufgebaut.

Die Strecke von Bukarest nach Budapest ist die am häufigsten verkehrende internationale Nachtzugverbindung in Europa. Es werden insgesamt drei Nachtzüge pro Richtung am Tag angeboten, vorbei eine Verbindung jeweils bis Wien fährt. Für jene die tagsüber gerne die Aussicht genießen, gibt es zwischen Bukarest und Budapest eine Verbindung die tagsüber fährt und 16 Stunden unterwegs ist.

Die Strecke führt einen durch die flachen Landschaften Ungarns und die Karpaten in Rumänien. Quer durch das Land, von Arad bis nach Braşov. Auf dem Weg gibt es wieder spannende Landschaften und viele Orte zu entdecken. Es lohnt sich auch vielleicht nicht in einer der Hauptstädte auszusteigen, sondern zu schauen, welche Orte auf dieser alten Bahnstrecke schlummern, in Träumen an die Zeiten, wo die Strecke noch die Schlagader der Region war.

An der Grenze des osTraums: Sofia / Bukarest – Istanbul

Obgleich die Türkei nicht im osTraum liegt, ist Istanbul trotzdem ein wichtiges Zentrum an der Peripherie zum osTraum und hat Südosteuropa durch viele Jahrzehnte hindurch beeinflusst. Der einstige Orient-Express legte den Großteil seiner Strecke im osTraum zurück. Wer also über die Grenzen des osTraums reisen will oder die Türkei als Landbrücke zum Kaukasus nutzen will, kann von Sofia (oder Bukarest) aus an den Rhodopen vorbei bis zum Bosporus fahren.

Zum Ende des osmanischen Reiches unter Abdul Hamid II wurde der Schienenausbau zu einer der wichtigsten wirtschaftlichen Prioritäten. So entstanden die heutigen Verbindungen in den osTraum. Im Osten der Türkei wartet man noch auf die Freigabe der Strecke von Kars nach Tbilisi und Baku für den Personenverkehr, womit in den kommenden Jahre eine neue Landbrücke über die Türkei zwischen dem Balkan und dem Kaukasus entstehen wird.

Natürlich kann ein Artikel nicht alle Bahnverbindungen abdecken und viele weitere sonderbare und schöne Strecken können noch entdeckt werden. Einige nennenswerte Strecken sind die etlichen Regionalverbindungen durch Slowenien, die Tatrabahn durch die Slowakei oder die endlosen Strecken durch die kasachische Steppe. Usbekistan hat mitunter einen der schnellsten Züge im osTraum und mit der RailBaltica soll es in nur wenigen Jahren möglich sein, von Berlin und Warschau aus alle baltischen Länder direkt zu erreichen. Es gibt auf jeden Fall noch viel zu sehen um das Leben in vollen Zügen zu genießen.

Damit es osTraum weiterhin gibt und Du coole Goodies bekommst,

unterstütze uns auf >>>Patreon<<<

osTraum auf Instagram

osTraum auf Facebook

osTraum auf Telegram

Titelfoto: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

It was springtime when my companion and I met up in Sarajevo, or Saraybosna, Turkish for Palace or Court of Bosnia. The city was once the westernmost frontier of the Ottoman Empire, which conquered it in the 14th century, leaving behind many familiar markings — the call to prayer from mosques, gushing fountains in courtyards and a myriad of Sufi traditions on display — making it a unique window into Islamic history in Europe.

Today, Bosnia also evokes memories of Europe’s worst genocide since WWII. And in recent reports, NATO considers it among the “partners at risk,” as Moscow’s meddling in its affairs has grown since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022.

Both its history and geopolitics are familiar to me. Having witnessed war and displacement during an itinerant childhood — in Algeria, Lebanon, Syria and Saudi Arabia — when my family aimed to stay ahead of war and economic stagnation, I wanted to see what a nation with parallel challenges to the Middle East might look like in Europe.

As I disembarked from the airport taxi near my hotel in the old city, I noticed the light from the streetlamp casting a gentle yellow hue on the cobblestoned street, which briefly caught the wheel of my suitcase. The scene captured an old-world charm that reminded me of other former Ottoman places like Aleppo, which sits ruined after Syria’s 13-year war. Perhaps, I thought, Sarajevo serves as an example of how a place once lost to war and besiegement can find its way back from the brink, despite facing internal fault lines that lend themselves to foreign exploitation.

It was still Ramadan during our time there. Just as we took our seats at a table for two outside, we heard the traditional iftar cannon fire in the distance, an iconic soft boom that remains ubiquitous across former Ottoman lands. About half of Bosnians identify as Muslim, according to census data. One-third identify as Christian Orthodox Serbs and 15% as Catholic Croats.

Our visit also coincided with the anniversary of the infamous siege of Sarajevo. The siege started a month or so after Bosnia-Herzegovina — one of six republics emerging from the breakup of Yugoslavia — declared its independence in March 1992 in a referendum recommended by the European Community. Bosniaks — as Bosnian Muslims refer to themselves — and Croats voted for it, but Serbian nationalists opposed independence and boycotted the vote, resenting the idea of becoming a minority in the newly formed Bosnia-Herzegovina. These divisions sounded familiar. People born of one nation and one tongue conceptualize themselves as separate from one another, more comfortably aligned with the culture of a foreign country than their own countryfolk. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, the country’s Serb nationalists identify as an extension of the state of Serbia, a longtime Russian ally, and refer to Bosniaks in the pejorative, calling them “Turks.” (The Serb nationalists later formed the Republika Srpska (RS), as a continuation of their warring party that was folded into the tripartite agreement among the country’s Bosniaks, Croats and Serbs at the Dayton Accords, hosted by then-U.S. President Bill Clinton in Ohio in 1995. Today RS remains a secessionist entity.)

In Sarajevo in 1992, despite the ethnic cleansing that had begun in the north, protests in the capital remained peaceful — until a fatal attack on April 5. That day corresponded with the holiday weekend commemorating both Sarajevo’s liberation from Nazi Germany and the day that Bosnia-Herzegovina’s independence was to come into effect. It was also the first day of Eid al-Fitr, a three-day holiday to mark the end of Ramadan through feasts and festivities with loved ones. Instead, two women were gunned down by sniper fire in a street not too far from where my companion and I were having our iftar, the image of their fallen bodies memorialized in a permanent exhibit at the Museum of Crimes Against Humanity and Genocide. They are wrapped in an embrace, for they tried to shelter each other from bullets. Today, they are remembered as the first victims of the siege, a sad point of departure from the peace that could have been.

What followed their death was three years and 10 months of besiegement — a year longer than the siege of Leningrad — making it, for a time, the longest modern-day siege of a capital city, until the siege of Ghouta (Damascus), which ended in 2018 after five years and one week. Having personally witnessed the latter, and as I learned more about the siege of Sarajevo, a morbid familiarity arose, for human cruelty has a homogeneous face, no matter the context. In both sieges there were sniper alleys where grandparents, mothers and children ran for their lives. Sometimes their fallen bodies were tended to by a loved one, who were also struck and killed by sniper fire. There were hungry families who stood waiting in bread lines but never got their turn. Rockets shelled people’s homes, reducing apartment buildings to their skeletal structure, broken concrete and twisted steel revealing lives interrupted.

Also familiar are the heroic acts carried out by ordinary people. Inside the genocide museum in Sarajevo, I read a story about Islam Dugum, a local marathon runner who left Sarajevo several times during the war and participated in various international competitions, including the Mediterranean Games, carrying the flag of Bosnia-Herzegovina. During these trips he would connect with refugees and exiles from his country and gather aid to bring back to Sarajevo, smuggling it through the Tunnel of Hope, which was built in the early months of the siege and remained the only way in or out of the city until the end of the war. Among the more privileged of his countrymen by virtue of being able to travel, Dugum found himself serving his compatriots by becoming a smuggling mule. It’s a story familiar to millions over recent decades and in so many conflicts. Ordinary civilians find they must smuggle on their person all manner of things: medicine, food and cash for the loved ones stuck back home and in desperate need of aid, no matter the risk of such transport. I’m now bearing witness to friends doing just that to help their loved ones stranded in Gaza, as I have similarly done for loved ones during the war in Syria.

One of the more deplorable details of the Sarajevo siege that I came upon is the documented macabre presence of “manhunting tourists,” a chilling term coined by film director Miran Zupanic in his documentary titled “Sarajevo Safari,” alleging a trend of rich foreigners who paid money to shoot at people in besieged Sarajevo. One such “tourist” was the late Russian writer Eduard Limonov, a Soviet dissident who immigrated to the United States, then returned to Russia in 1991 and founded an ultranationalist party. Though it’s unclear if he paid for the sordid opportunity, he was filmed at a Serbian shooting post on June 22, 1992, accepting an invitation by Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic to fire a machine gun, aiming it at the streets of Sarajevo below. He fired several rounds, stopping briefly to allow Karadzic to adjust the gun’s tripod mount before carrying on with the task. My eyes lingered on the TV screening this footage on a loop inside the genocide museum, and I tried to understand why — and how — a fellow writer, whose job requires cultivating a sensitivity to the human condition, could so easily steel himself to snuff a life in cold blood.

War, I find, upends society, not just by leaving a trail of destruction but also by forcing to the surface what otherwise remains hidden, like the way a storm dredges up muck from a riverbed. In this muck one finds society’s moral malaise, the covert and base parts of human nature cajoled to the surface by violence and calamity. War can also bring out the best of humanity. During the war in Syria, almost anywhere I looked, I saw both: People who were emaciated from living under siege shared the little food they had in their possession with others, and people who had no good reason to hate aimed their gun and killed a stranger. One time I saw a crazed gunman aim his semiautomatic weapon and shoot a donkey that was minding its own business. Another time I was stuck in traffic behind a truckload of armed militia members when I noticed one of them pointing his rifle at me from his perch on the truck bed, glaring down at me and smirking, hoping perhaps to meet my eye behind my sunglasses in whatever sick sense of power he felt. Thankfully, traffic moved and something else distracted him.

My companion and I rented a car and drove the backroads, stopping frequently to take hikes in the woods, which are pristine and beautiful throughout Bosnia. Public spigots offered up crisp water from the streams. Around us small family-owned farms raised lamb and kept bees. The summer heat had not yet arrived, so on the surface everything seemed idyllic.

But a startling aspect of driving through Bosnia-Herzegovina is the demarcation of territory by the secessionist Republika Srpska. We saw this often: the RS flag (which resembles the Russian one) hoisted on a pole atop a Serbian war memorial or public square visible upon entering a town, announcing RS-controlled territory. These territories, which take up much of the northern and southeastern regions of Bosnia-Herzegovina, continue to cultivate a distinct and separate identity steeped in Serbian nationalism, teaching their own curricula in schools, including their version of the war and the siege, in which they largely deny the crimes committed in the name of Serbs. Serbia has been pushing to unify its school curricula with that of RS, which would exacerbate an already precarious situation of a Russian-backed Serbian nation within the state of Bosnia-Herzegovina, a country that hopes to one day join the European Union. (However, many locals say this goal is too lofty given their country’s dire political and economic structure, even without the complication of a ministate within a state.) Even roadside signage of town names reveals a low-grade battleground for territoriality, with graffiti blacking out either the town’s Cyrillic or Latin spelling. Bosnia-Herzegovina uses Latin letters while Serbia and RS use Cyrillic, though both, as well as Croats, speak the same Slavic language, albeit with slightly different dialects.

These divisions, along with an unabashedly corrupt, multiconfessional government, reminded me of the state of affairs in Lebanon, where the authorities have also failed to unify a school curriculum that teaches a national narrative. By relegating the retelling of the country’s history and its civil war to the whims of sectarian narrators, the promise of another sectarian conflict remains ever within sight. And so too is the case, it seems, in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

On May 24, the U.N. General Assembly voted to establish an annual day of remembrance for the Srebrenica massacre, much to the chagrin of Serbia and Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik, who promptly held a press conference and declared: “There was no genocide in Srebrenica.” Jasmin Mujanovic, political scientist and author of “The Bosniaks: Nationhood After Genocide,” told New Lines that in reaction to the General Assembly vote, RS special police forces were seen deployed around Srebrenica in a show of force. “This was very clearly intended as an attempt to intimidate, harass and terrorize the local population having to do with the U.N. vote.” Mujanovic added that there’s been “an alarming upsurge in attacks” against Bosniaks returning to their homes in the Serb-run northern and eastern parts of Bosnia-Herzegovina, after having been expelled during the war. “In general, the day-to-day situation for the Bosniak community in parts of RS has deteriorated and there’s a pervasive culture of fear that permeates, as Dodik rhetoric and politics have escalated over the past year and a half.”

As our visit to Bosnia-Herzegovina was coming to an end, it was finally time to bear witness to Srebrenica. I had been to other places where crimes against humanity were committed, where little or no justice and reconciliation occurred, where a terrible truth remains unacknowledged, considered a mere “opinion” depending on “whose side you’re on,” or a fact that no one dares utter.

In the mid-2000s, I visited the Syrian town of Hama. It was some years after the infamous 1982 massacre perpetrated by the Assad regime against a local uprising, killing en masse over 20,000 people including, as is typical in genocidal acts, entire families. What struck me most about the place, as I walked through its streets, was how guarded the people were, how reluctant they seemed to greet a stranger and how their suspicious demeanor differed from the lackadaisical hospitality found elsewhere in the country. I recall one aspect of Hama that was especially chilling: When I found myself walking atop a mound surrounded by relatively new construction. It was the site of the mass grave where the regime dumped the dead bodies after the mass killing, then covered them with dirt and built a parking lot. The silence that ensued, the lack of international outcry without consequences to the perpetrators or justice to the victims, hung so heavy in the air. Nowadays in Syria, along with many towns in Iraq, Lebanon and elsewhere in the region, not to mention the ongoing war in Gaza, Hama is merely one among many such sad places.

Would Srebrenica have a similarly haunted feeling, I wondered?

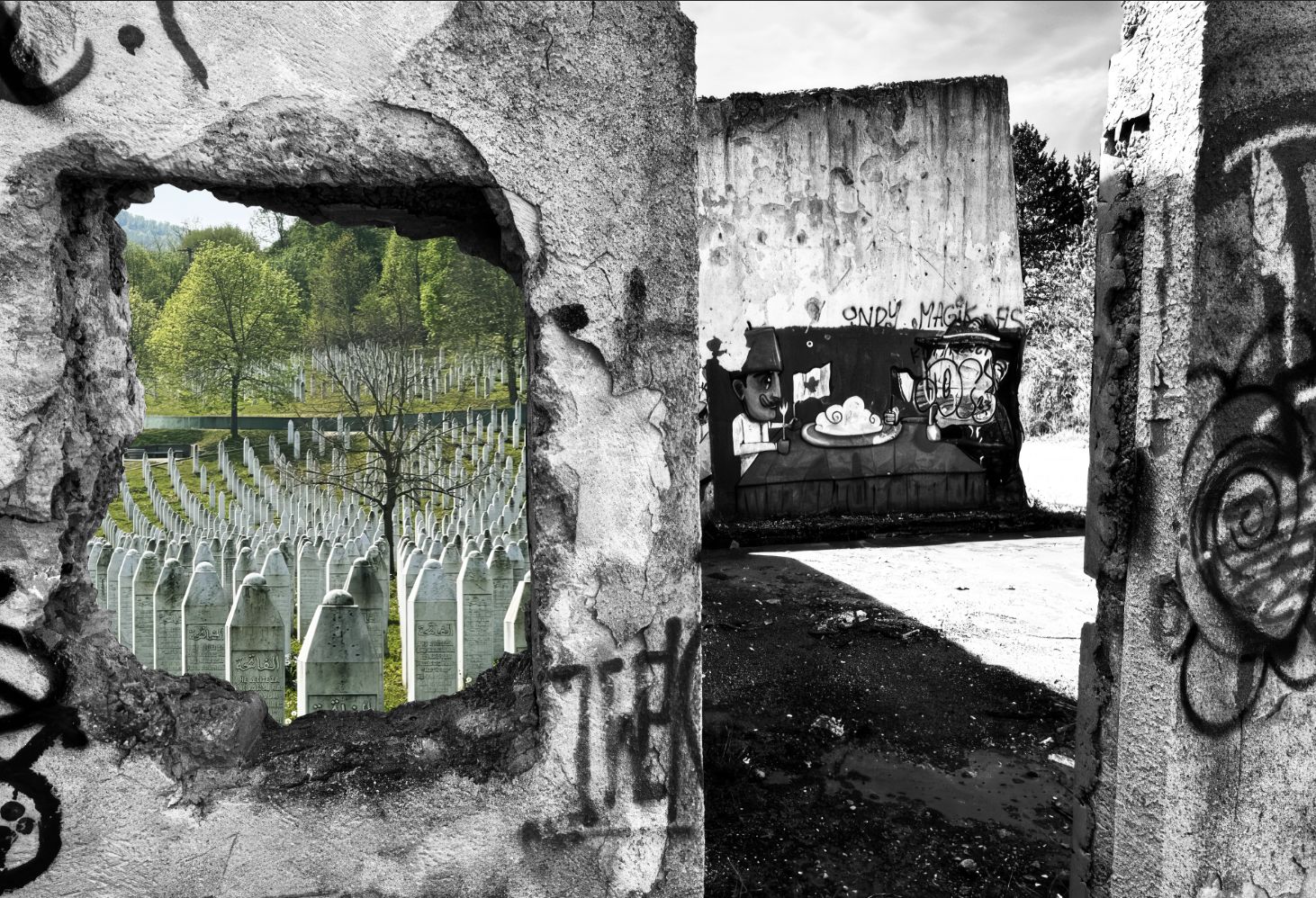

It was impossible to miss the Srebrenica Genocide Memorial by the roadside upon our approach to the town, with over 6,000 marked graves, including a few fresh ones. As unmarked graves continue to be found all over the country, their contents are exhumed and identified before being re-buried at the memorial cemetery. It happened to be the second day of Eid al-Fitr when my companion and I found ourselves there. Around us a constant trickle of families arrived to visit their dead loved ones, as is customary during Eid for many Muslims, for as always when the deed is done, death is hardest on the living.

Across the street stood derelict structures that once housed the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR), where one of the many failures of the international community tragically unfolded. In the early hours of July 6, 1995, Serb forces attacked Srebrenica and the Dutch Battalion peacekeepers (Dutchbat) who were stationed there as part of the UNPROFOR. Over the next few days, the villages around the town of Srebrenica and the U.N. outpost fell to Serbian forces, despite the Dutchbat’s repeated requests for support from the U.N. and NATO — support that never came for reasons that remain unclear. As Serbian forces tightened their siege of the area, Bosniaks fled on foot, making their way to the town of Srebrenica, which fell to the Serbs on July 11. Serbian forces made no secret of their intentions, nor of the long-running nature of this conflict.

“The time has come to take revenge on the Turks here,” Bosnian Serb Gen. Ratko Mladic announced upon entering the city, which the U.N. had designated a safe zone. Mladic was referencing the Battle of Kosovo, where the Ottomans defeated a Serbian prince in 1389.

More displacement followed. Bosniak men and boys formed a column and set off into the woods, aiming to get through Serb territory to the safety of Bosnian-Herzegovinian territory. Some 30,000 women, children and elderly started moving toward the U.N. compound, seeking haven and humanitarian assistance.

The Dutch soldiers tried to help. They cut an opening in the fence of their compound to allow in as many refugees as they could, which, given the limited space, overflowing toilets and dwindling food and medical supplies, was not many. They kept requesting support from the international community — humanitarian airdrops and NATO air cover that never came. (The Dutch government has recently apologized to Dutchbat veterans, acknowledging that they had been sent on a mission “that ultimately proved impossible to carry out,” as the world failed the victims of the Srebrenica genocide “in the most terrible way.”)

There is footage of Mladic addressing the refugees, promising that none would be harmed as they were about to be (forcibly) transported in busloads out of Serbian territory — promises he had no intention of keeping. He suggested that the women and children go first — for chivalry’s sake, he implied. But in reality, he had other plans for the men.

The buses for the evacuation started to arrive, and with the Dutchbat peacekeepers standing by, the Serbs began to separate the men and boys from the rest of the refugees. The Serbs also captured thousands of Bosniak men and boys from the column that had struck out on foot into the woods.

Over the next few days, Serbian forces systematically executed in cold blood some 8,000 Bosniak men and boys. They did this in meadows and on military farms, in abandoned school buildings and inside former cultural centers. Survivors later told their horror stories during testimonies at The Hague.

My companion and I managed to enter the nearly abandoned compound, which is closed to the public, and walked through some of its precariously unsound structures that have remained standing and unchanged since the war. Inside one warehouse, a dark water-filled square pit stood out in the otherwise smooth but filthy concrete floor. An animal the size of a pig floated on its surface, bloated and dead for some unknown amount of time. It seemed an apt metaphor for the horrors this place had witnessed — horrors that U.N. peacekeepers had been powerless to prevent.

As Bosnia-Herzegovina continues to confront genocide denialism, successionist factionalism and increased foreign meddling, what does the future hold? Is it a failed state like some of the countries I once called home?

I put this question to Peter Lippman, author of “Surviving the Peace: The Struggle for Postwar Recovery in Bosnia-Herzegovina.”

“The short answer,” he said, “is that Bosnia-Herzegovina is a particular form of dysfunctional state ruled by corrupt domestic politicians under the full enabling of international officials.” Lippman added that the country is still “in its postwar form and has not yet had the chance to be a state, so it cannot be a failed state in the classic definition.”

Perhaps one sentiment that my companion and I overheard on a hike captures the overarching mood in the country. It came as a response to tourists wondering aloud, in English, whether they could park their car near the trailhead.

“Yes, yes, it’s OK. A policeman comes and you give him 10 marks,” a local, middle-aged man assured them with a chuckle. “This is Bosnia. It’s the wild, wild west.”

And that, too, rang familiar.

The post In Postwar Sarajevo, the Similarities With Middle East Turmoil Resonate appeared first on New Lines Magazine.

“This will destroy China forever,” a young Taiwanese cadet thought as he sat in rapt attention. The renowned historian Arnold J. Toynbee was on stage, delivering a lecture at Washington and Lee University on “A Changing World in Light of History.” The talk plowed the professor’s favorite field of inquiry: the genesis, growth, death, and disintegration of human civilizations, immortalized in his magnum opus A Study of History. Tonight’s talk threw the spotlight on China.

China was Toynbee’s outlier: Ancient as Egypt, it was a civilization that had survived the ravages of time. The secret to China’s continuity, he argued, was character-based Chinese script. Character-based script served as a unifying medium, placing guardrails against centrifugal forces that might otherwise have ripped this grand and diverse civilization apart. This millennial integrity was now under threat. Indeed, as Toynbee spoke, the government in Beijing was busily deploying Hanyu pinyin, a Latin alphabet–based Romanization system.

The Taiwanese cadet listening to Toynbee was Chan-hui Yeh, a student of electrical engineering at the nearby Virginia Military Institute (VMI). That evening with Arnold Toynbee forever altered the trajectory of his life. It changed the trajectory of Chinese computing as well, triggering a cascade of events that later led to the formation of arguably the first successful Chinese IT company in history: Ideographix, founded by Yeh 14 years after Toynbee stepped offstage.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Chinese computing underwent multiple sea changes. No longer limited to small-scale laboratories and solo inventors, the challenge of Chinese computing was taken up by engineers, linguists, and entrepreneurs across Asia, the United States, and Europe—including Yeh’s adoptive home of Silicon Valley.

Chan-hui Yeh’s IPX keyboard featured 160 main keys, with 15 characters each. A peripheral keyboard of 15 keys was used to select the character on each key. Separate “shift” keys were used to change all of the character assignments of the 160 keys. Computer History Museum

Chan-hui Yeh’s IPX keyboard featured 160 main keys, with 15 characters each. A peripheral keyboard of 15 keys was used to select the character on each key. Separate “shift” keys were used to change all of the character assignments of the 160 keys. Computer History Museum

The design of Chinese computers also changed dramatically. None of the competing designs that emerged in this era employed a QWERTY-style keyboard. Instead, one of the most successful and celebrated systems—the IPX, designed by Yeh—featured an interface with 120 levels of “shift,” packing nearly 20,000 Chinese characters and other symbols into a space only slightly larger than a QWERTY interface. Other systems featured keyboards with anywhere from 256 to 2,000 keys. Still others dispensed with keyboards altogether, employing a stylus and touch-sensitive tablet, or a grid of Chinese characters wrapped around a rotating cylindrical interface. It’s as if every kind of interface imaginable was being explored except QWERTY-style keyboards.

IPX: Yeh’s 120-dimensional hypershift Chinese keyboard

Yeh graduated from VMI in 1960 with a B.S. in electrical engineering. He went on to Cornell University, receiving his M.S. in nuclear engineering in 1963 and his Ph.D. in electrical engineering in 1965. Yeh then joined IBM, not to develop Chinese text technologies but to draw upon his background in automatic control to help develop computational simulations for large-scale manufacturing plants, like paper mills, petrochemical refineries, steel mills, and sugar mills. He was stationed in IBM’s relatively new offices in San Jose, Calif.

Toynbee’s lecture stuck with Yeh, though. While working at IBM, he spent his spare time exploring the electronic processing of Chinese characters. He felt convinced that the digitization of Chinese must be possible, that Chinese writing could be brought into the computational age. Doing so, he felt, would safeguard Chinese script against those like Chairman Mao Zedong, who seemed to equate Chinese modernization with the Romanization of Chinese script. The belief was so powerful that Yeh eventually quit his good-paying job at IBM to try and save Chinese through the power of computing.

Yeh started with the most complex parts of the Chinese lexicon and worked back from there. He fixated on one character in particular: ying 鷹 (“eagle”), an elaborate graph that requires 24 brushstrokes to compose. If he could determine an appropriate data structure for such a complex character, he reasoned, he would be well on his way. Through careful analysis, he determined that a bitmap comprising 24 vertical dots and 20 horizontal dots would do the trick, taking up 60 bytes of memory, excluding metadata. By 1968, Yeh felt confident enough to take the next big step—to patent his project, nicknamed “Iron Eagle.” The Iron Eagle project quickly garnered the interest of the Taiwanese military. Four years later, with the promise of Taiwanese government funding, Yeh founded Ideographix, in Sunnyvale, Calif.

A single key of the IPX keyboard contained 15 characters. This key contains the character zhong (中 “central”), which is necessary to spell “China.” MIT Press

A single key of the IPX keyboard contained 15 characters. This key contains the character zhong (中 “central”), which is necessary to spell “China.” MIT Press

The flagship product of Ideographix was the IPX, a computational typesetting and transmission system for Chinese built upon the complex orchestration of multiple subsystems.

The marvel of the IPX system was the keyboard subsystem, which enabled operators to enter a theoretical maximum of 19,200 Chinese characters despite its modest size: 59 centimeters wide, 37 cm deep, and 11 cm tall. To achieve this remarkable feat, Yeh and his colleagues decided to treat the keyboard not merely as an electronic peripheral but as a full-fledged computer unto itself: a microprocessor-controlled “intelligent terminal” completely unlike conventional QWERTY-style devices.

Seated in front of the IPX interface, the operator looked down on 160 keys arranged in a 16-by-10 grid. Each key contained not a single Chinese character but a cluster of 15 characters arranged in a miniature 3-by-5 array. Those 160 keys with 15 characters on each key yielded 2,400 Chinese characters.

The process of typing on the IPX keyboard involved using a booklet of characters used to depress one of 160 keys, selecting one of 15 numbers to pick a character within the key, and using separate “shift” keys to indicate when a page of the booklet was flipped. MIT Press

The process of typing on the IPX keyboard involved using a booklet of characters used to depress one of 160 keys, selecting one of 15 numbers to pick a character within the key, and using separate “shift” keys to indicate when a page of the booklet was flipped. MIT Press

Chinese characters were not printed on the keys, the way that letters and numbers are emblazoned on the keys of QWERTY devices. The 160 keys themselves were blank. Instead, the 2,400 Chinese characters were printed on laminated paper, bound together in a spiral-bound booklet that the operator laid down flat atop the IPX interface.The IPX keys weren’t buttons, as on a QWERTY device, but pressure-sensitive pads. An operator would push down on the spiral-bound booklet to depress whichever key pad was directly underneath.

To reach characters 2,401 through 19,200, the operator simply turned the spiral-bound booklet to whichever page contained the desired character. The booklets contained up to eight pages—and each page contained 2,400 characters—so the total number of potential symbols came to just shy of 20,000.

For the first seven years of its existence, the use of IPX was limited to the Taiwanese military. As years passed, the exclusivity relaxed, and Yeh began to seek out customers in both the private and public sectors. Yeh’s first major nonmilitary clients included Taiwan’s telecommunication administration and the National Taxation Bureau of Taipei. For the former, the IPX helped process and transmit millions of phone bills. For the latter, it enabled the production of tax return documents at unprecedented speed and scale. But the IPX wasn’t the only game in town.

Loh Shiu-chang, a professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, developed what he called “Loh’s keyboard” (Le shi jianpan 樂氏鍵盤), featuring 256 keys. Loh Shiu-chang

Loh Shiu-chang, a professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, developed what he called “Loh’s keyboard” (Le shi jianpan 樂氏鍵盤), featuring 256 keys. Loh Shiu-chang

Mainland China’s “medium-sized” keyboards

By the mid-1970s, the People’s Republic of China was far more advanced in the arena of mainframe computing than most outsiders realized. In July 1972, just months after the famed tour by U.S. president Richard Nixon, a veritable blue-ribbon committee of prominent American computer scientists visited the PRC. The delegation visited China’s main centers of computer science at the time, and upon learning what their counterparts had been up to during the many years of Sino-American estrangement, the delegation was stunned.

But there was one key arena of computing that the delegation did not bear witness to: the computational processing of Chinese characters. It was not until October 1974 that mainland Chinese engineers began to dive seriously into this problem. Soon after, in 1975, the newly formed Chinese Character Information Processing Technology Research Office at Peking University set out upon the goal of creating a “Chinese Character Information Processing and Input System” and a “Chinese Character Keyboard.”

The group evaluated more than 10 proposals for Chinese keyboard designs. The designs fell into three general categories: a large-keyboard approach, with one key for every commonly used character; a small-keyboard approach, like the QWERTY-style keyboard; and a medium-size keyboard approach, which attempted to tread a path between these two poles.

Peking University’s medium-sized keyboard design included a combination of Chinese characters and character components, as shown in this explanatory diagram. Public Domain

Peking University’s medium-sized keyboard design included a combination of Chinese characters and character components, as shown in this explanatory diagram. Public Domain

The team leveled two major criticisms against QWERTY-style small keyboards. First, there were just too few keys, which meant that many Chinese characters were assigned identical input sequences. What’s more, QWERTY keyboards did a poor job of using keys to their full potential. For the most part, each key on a QWERTY keyboard was assigned only two symbols, one of which required the operator to depress and hold the shift key to access. A better approach, they argued, was the technique of “one key, many uses”— yijian duoyong—assigning each key a larger number of symbols to make the most use of interface real estate.

The team also examined the large-keyboard approach, in which 2,000 or more commonly used Chinese characters were assigned to a tabletop-size interface. Several teams across China worked on various versions of these large keyboards. The Peking team, however, regarded the large-keyboard approach as excessive and unwieldy. Their goal was to exploit each key to its maximum potential, while keeping the number of keys to a minimum.

After years of work, the team in Beijing settled upon a keyboard with 256 keys, 29 of which would be dedicated to various functions, such as carriage return and spacing, and the remaining 227 used to input text. Each keystroke generated an 8-bit code, stored on punched paper tape (hence the choice of 256, or 28, keys). These 8-bit codes were then translated into a 14-bit internal code, which the computer used to retrieve the desired character.

In their assignment of multiple characters to individual keys, the team’s design was reminiscent of Ideographix’s IPX machine. But there was a twist. Instead of assigning only full-bodied, stand-alone Chinese characters to each key, the team assigned a mixture of both Chinese characters and character components. Specifically, each key was associated with up to four symbols, divided among three varieties:

- full-body Chinese characters (limited to no more than two per key)

- partial Chinese character components (no more than three per key)

- the uppercase symbol, reserved for switching to other languages (limited to one per key)

In all, the keyboard contained 423 full-body Chinese characters and 264 character components. When arranging these 264 character components on the keyboard, the team hit upon an elegant and ingenious way to help operators remember the location of each: They treated the keyboard as if it were a Chinese character itself. The team placed each of the 264 character components in the regions of the keyboard that corresponded to the areas where they usually appeared in Chinese characters.

In its final design, the Peking University keyboard was capable of inputting a total of 7,282 Chinese characters, which in the team’s estimation would account for more than 90 percent of all characters encountered on an average day. Within this character set, the 423 most common characters could be produced via one keystroke; 2,930 characters could be produced using two keystrokes; and a further 3,106 characters could be produced using three keystrokes. The remaining 823 characters required four or five keystrokes.

The Peking University keyboard was just one of many medium-size designs of the era. IBM created its own 256-key keyboard for Chinese and Japanese. In a design reminiscent of the IPX system, this 1970s-era keyboard included a 12-digit keypad with which the operator could “shift” between the 12 full-body Chinese characters outfitted on each key (for a total of 3,072 characters in all). In 1980, Chinese University of Hong Kong professor Loh Shiu-chang developed what he called “Loh’s keyboard” (Le shi jianpan 樂氏鍵盤), which also featured 256 keys.

But perhaps the strangest Chinese keyboard of the era was designed in England.

The cylindrical Chinese keyboard

On a winter day in 1976, a young boy in Cambridge, England, searched for his beloved Meccano set. A predecessor of the American Erector set, the popular British toy offered aspiring engineers hours of modular possibility. Andrew had played with the gears, axles, and metal plates recently, but today they were nowhere to be found.

Wandering into the kitchen, he caught the thief red-handed: his father, the Cambridge University researcher Robert Sloss. For three straight days and nights, Sloss had commandeered his son’s toy, engrossed in the creation of a peculiar gadget that was cylindrical and rotating. It riveted the young boy’s attention—and then the attention of the Telegraph-Herald, which dispatched a journalist to see it firsthand. Ultimately, it attracted the attention and financial backing of the U.K. telecommunications giant Cable & Wireless.

Robert Sloss was building a Chinese computer.

The elder Sloss was born in 1927 in Scotland. He joined the British navy, and was subjected to a series of intelligence tests that revealed a proclivity for foreign languages. In 1946 and 1947, he was stationed in Hong Kong. Sloss went on to join the civil service as a teacher and later, in the British air force, became a noncommissioned officer. Owing to his pedagogical experience, his knack for language, and his background in Asia, he was invited to teach Chinese at Cambridge and appointed to a lectureship in 1972.

At Cambridge, Sloss met Peter Nancarrow. Twelve years Sloss’s junior, Nancarrow trained as a physicist but later found work as a patent agent. The bearded 38-year-old then taught himself Norwegian and Russian as a “hobby” before joining forces with Sloss in a quest to build an automatic Chinese-English translation machine.

In 1976, Robert Sloss and Peter Nancarrow designed the Ideo-Matic Encoder, a Chinese input keyboard with a grid of 4,356 keys wrapped around a cylinder. PK Porthcurno

In 1976, Robert Sloss and Peter Nancarrow designed the Ideo-Matic Encoder, a Chinese input keyboard with a grid of 4,356 keys wrapped around a cylinder. PK Porthcurno

They quickly found that the choke point in their translator design was character input— namely, how to get handwritten Chinese characters, definitions, and syntax data into a computer.

Over the following two years, Sloss and Nancarrow dedicated their energy to designing a Chinese computer interface. It was this effort that led Sloss to steal and tinker with his son’s Meccano set. Sloss’s tinkering soon bore fruit: a working prototype that the duo called the “Binary Signal Generator for Encoding Chinese Characters into Machine-compatible form”—also known as the Ideo-Matic Encoder and the Ideo-Matic 66 (named after the machine’s 66-by-66 grid of characters).

Each cell in the machine’s grid was assigned a binary code corresponding to the X-column and the Y-row values. In terms of total space, each cell was 7 millimeters squared, with 3,500 of the 4,356 cells dedicated to Chinese characters. The rest were assigned to Japanese syllables or left blank.

The distinguishing feature of Sloss and Nancarrow’s interface was not the grid, however. Rather than arranging their 4,356 cells across a rectangular interface, the pair decided to wrap the grid around a rotating, tubular structure. The typist used one hand to rotate the cylindrical grid and the other hand to move a cursor left and right to indicate one of the 4,356 cells. The depression of a button produced a binary signal that corresponded to the selected Chinese character or other symbol.

The Ideo-Matic Encoder was completed and delivered to Cable & Wireless in the closing years of the 1970s. Weighing in at 7 kilograms and measuring 68 cm wide, 57 cm deep, and 23 cm tall, the machine garnered industry and media attention. Cable & Wireless purchased rights to the machine in hopes of mass-manufacturing it for the East Asian market.

QWERTY’s comeback

The IPX, the Ideo-Matic 66, Peking University’s medium-size keyboards, and indeed all of the other custom-built devices discussed here would soon meet exactly the same fate—oblivion. There were changes afoot. The era of custom-designed Chinese text-processing systems was coming to an end. A new era was taking shape, one that major corporations, entrepreneurs, and inventors were largely unprepared for. This new age has come to be known by many names: the software revolution, the personal-computing revolution, and less rosily, the death of hardware.

From the late 1970s onward, custom-built Chinese interfaces steadily disappeared from marketplaces and laboratories alike, displaced by wave upon wave of Western-built personal computers crashing on the shores of the PRC. With those computers came the resurgence of QWERTY for Chinese input, along the same lines as the systems used by Sinophone computer users today—ones mediated by a software layer to transform the Latin alphabet into Chinese characters. This switch to typing mediated by an input method editor, or IME, did not lead to the downfall of Chinese civilization, as the historian Arnold Toynbee may have predicted. However, it did fundamentally change the way Chinese speakers interact with the digital world and their own language.

This article appears in the June 2024 print issue.

1. I am smiling at the camera, one finger to my lips as though I’m holding in a secret. You are turned towards me, kissing my skin. Unseen, your dick is inside me, filling my ass. A patch of sweat glistens on my shoulder, I don’t know if it’s yours or mine.

When I arrived at yours, after a long drive, you said,

“I’m going to cook for you. And then I’d like to fuck you. Is that okay?”

I wore your collar for the first time. I lowered my gaze and did as I was told. We fucked in your bed, on your sofa, on the stairs, in the garden.

I drove home the next day, aching and delighted.

2. Me, naked, holding up bed restraints at a hotel window.

“Stand there,” you’d said.

It was daytime and the street was busy.

“But people will see.”

“Do as you’re told.”

I did as I was told. I felt glorious, unashamed on display. I loved it. I had told you once that I never thought I’d be able to submit. With you it was easy. It was beautiful. I was beautiful.

3. A gif, me naked on a swing.

We’d gone to a local park in the darkness.

“Take your clothes off.”

“Yes, N,” I’d said.

I was joyous. I was a different me from the woman cloaked in self-loathing for much of her life. I felt so free.

4. A series of photos of our smiling faces.

We are both grinning. We’re happy.

We’d spent the weekend away, a trip booked for a while and threatened by the pandemic. We’d been to a gig, an act we had loved as teenagers, a soundtrack to our connection. In the bar, you took photo after photo, laughing as I failed to look in the right direction. In some, you’re kissing me.

During the gig, I kept turning round to look at you. You were always smiling and so was I. I couldn’t believe I was there with you, listening to this. Afterwards, you bought me two mugs, souvenirs of the music.

Back in the room we were renting, you decorated my skin with bruises. I was alive with the pain you inflicted.

I took photos when I got home, thrilled with the purple splashes, the souvenirs of us.

5. You on my sofa, drinking red wine.

You’re naked. My hand is in shot, holding your dick, my nails painted dark green. Your face is turned towards the TV.

That evening, I went on cam with you. You’d turned up at mine, tired and hot. We had a bath together. There are more photos from the night. Me on my knees, gazing up at you as I sucked your dick. Oh, how I loved to suck your dick. I felt powerful, making you groan. I loved your hands in my hair, pulling me in, pushing yourself deeper into my mouth.

You told me, when we were younger, that I had ‘fellatio lips.’ I ached to use them on you now.

6. One from long ago.

You’re standing behind me, holding me. I’m wearing an enormous stripy t-shirt. We’re both smiling at the camera.

I found some old negatives and got them made into prints. I was excited to show you. We were 19, living together in a flat we shared with my brother. Behind us is a bookcase, adorned with cuddly toys, rescued from my repossessed family home. We had to be so grown up. We had a lot of fun.

After we first met, I kept you at a distance for as long as I could, ashamed of my life, ashamed of myself. I didn’t want you to see how I lived. You wrote me a letter, saying you couldn’t stop thinking about me. I couldn’t believe that you, gorgeous and brilliant you, could feel that way.

I fell in love.

7. You, bare-chested, turned away from the camera.

“Stay still,” I’d said before taking the photo. You look handsome, lit up by candlelight and the glow of my television.

You’d come to stay for your birthday. I wrapped myself in a bow and brought you breakfast in bed. Your dick was hard at the sight of me, so I put your breakfast aside.

I so liked you being in my house. You helped scare away the ghosts that haunted the corners of my home, my body, my mind.

Afterwards, you tell me this is one of the best photos ever taken of you. It’s my favourite. You, captured through my eyes. You are so alive and alight.

8. The last photo I have of us together.

You’re raising a glass of espresso martini. Off camera, one of your other partners. The two of you welcomed me into your home. I was happy to be with you and my metamour, getting to know her better, feeling cared for. We all spent the evening together, watching films, comfortable in our connection. Laughing.

I sent the photo to my brother, “Look who I’m with!” My brother said to say hi. He thinks of you fondly.

I text him back and tell him I love you.

- by Aeon Video